# The Truth Behind the Marshmallow Test: Insights and Misconceptions

Written on

Chapter 1: Understanding the Marshmallow Test

Have you heard of the Marshmallow Test? If not, here's a quick overview. In 1972, Walter Mischel, a psychologist at Stanford University, conducted a series of experiments where children were offered a marshmallow on a plate. They were told they could either eat it immediately or wait for a little while to receive two marshmallows when the researcher returned after approximately 15 minutes.

How long could these children resist the temptation? The findings indicated that those who managed to wait longer tended to achieve better life outcomes many years later. This led to a whole movement focused on teaching children the valuable skill of delayed gratification, which was believed to contribute to a more successful life.

However, the situation is more complicated than it appears.

Section 1.1: The Pitfall of Simplistic Conclusions

Subsequent research has shown that while there is a link between the ability to delay gratification in childhood and success later in life, this does not imply a direct cause-and-effect relationship. A study published in May 2018, titled “Revisiting the Marshmallow Test: A Conceptual Replication Investigating Links Between Early Delay of Gratification and Later Outcomes,” shed new light on this issue.

The original 1972 research led to the belief that teaching children delayed gratification would yield positive results. However, it turns out that the outcomes were more closely tied to the children's life circumstances rather than the skill itself. In essence, those who excelled in the test were likely to have advantages in their environment, rather than simply having mastered the art of waiting. Thus, the idea that this skill was a shortcut to success has been called into question.

Section 1.2: A New Perspective on Delay of Gratification

In a fascinating study published on January 20, 2020, researchers Rebecca Koomen, Sebastian Grueneisen, and Esther Herrmann from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology modified the classic Marshmallow Test. In their experiment, they paired over 200 five- and six-year-olds and had them engage in a balloon toss game to ease into the testing environment. Afterward, the children were placed in separate rooms, each presented with a cookie.

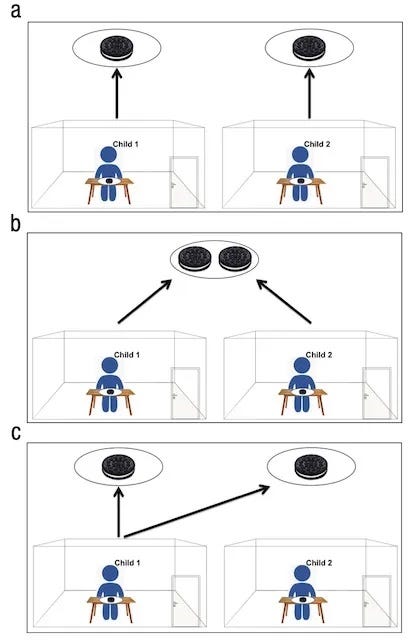

Some children operated under a solo condition, relying solely on their self-control to earn a second cookie, while others participated in a cooperative condition where both needed to resist eating the cookie to receive a reward. This interdependence added an element of risk since the success of one child depended on the other’s restraint.

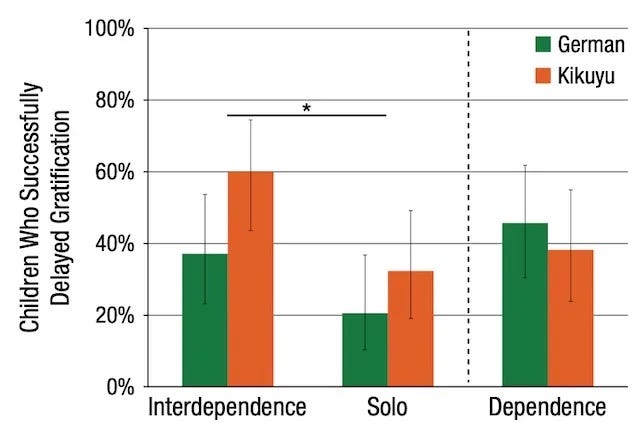

The researchers tested both German and Kikuyu children from Kenya, aiming to uncover cultural differences in their responses. The findings indicated that Kikuyu children were more inclined to delay gratification than their German peers, particularly in the interdependence scenario.

Chapter 2: Cultural Influences on Delayed Gratification

The study highlighted three variations of the experiment:

- Solo condition: Two children were each given a cookie; their outcomes were independent of one another.

- Interdependence condition: Both children needed to wait to receive a second cookie, relying on each other's self-control.

- Dependence condition: Children believed their partner's actions impacted their own outcomes, although this was not the case.

The results revealed that children from both cultures were more likely to delay gratification when their partner's outcome was linked to their own efforts, demonstrating a universal tendency toward cooperative behavior.

The researchers proposed that cultural differences in socialization might explain why Kikuyu children performed better. Kikuyu parents often emphasize obedience and self-regulation, which may better equip their children to resist immediate temptations.

Key Point: A Universal Observational Truth

Although the study does not definitively explain cultural disparities, it emphasizes that children across cultures are more motivated to delay gratification in cooperative contexts. This suggests that the motivation for cooperation is deeply ingrained in human psychology, even from a young age.

Study Author Insights

Sebastian Grueneisen remarked on the significance of their findings, emphasizing that children’s ability to delay gratification is influenced by the cooperative context, even when communication isn't possible. Rebecca Koomen noted that children might be motivated by a sense of obligation to their partner, indicating the strong psychological underpinnings of cooperation.

In conclusion, these insights reveal that from early childhood, humans are inherently equipped to engage in cooperative behaviors, and the ability to delay gratification is just one aspect of this complex social interplay. Understanding these dynamics is essential, especially in today's polarized social climate.

For further reading on this topic, explore the following resources:

- Wikipedia — Stanford marshmallow experiment

- Association for Psychological Science (Jan 2020) — “Marshmallow Test” Redux: New Research Reveals Children Show Better Self-Control When They Depend on Each Other

- Study in Psychological Science (9th Jan 2020) — Children Delay Gratification for Cooperative Ends